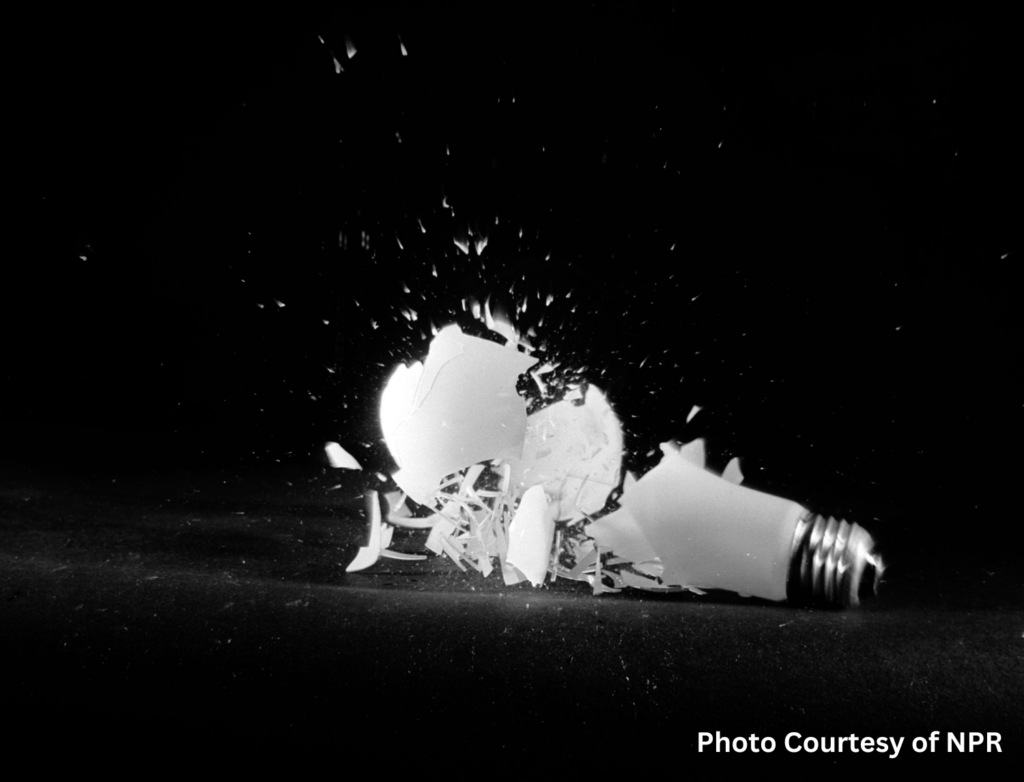

In the realm of lighting industry history, few stories are as intriguing and controversial as that of the Phoebus Cartel. This secretive alliance of major light bulb manufacturers in the early 20th Century not only shaped the lighting industry but also raised important questions about corporate ethics, consumer rights, and the lengths to which companies will go to protect their profits.

On December 23, 1924, a group of international businessmen gathered in Geneva, Switzerland for a meeting that would alter the lighting world for decades to come. Meeting attendees represented the four major lighting manufacturers: Germany’s Osram, Philips from the Netherlands, the French company Compagnie des Lampes, and General Electric from the United States (represented by their European subsidiaries).

On the cusp of the Christmas holiday, these companies formed the Phoebus Cartel in response to the growing competition in the light bulb market, particularly with the advent of longer-lasting incandescent bulbs. The members recognized that if they did not act together, their profits would be threatened by innovations that could lead to a significant reduction in bulb sales. So, they carved up the market and created the first consumer products cartel with a global reach.

The primary goal of the Phoebus Cartel was to control the production and distribution of light bulbs. To achieve this, the Cartel implemented several key strategies:

1. Standardization of Product Lifespan: The Cartel agreed to limit the lifespan of light bulbs to 1,000 hours. This was a significant reduction from the 2,500 hours that some bulbs could last. By doing so, they ensured that consumers would need to replace their bulbs more frequently, thus boosting sales. By coordinating this shorter light bulb life, the Cartel hatched the industrial business strategy now known as “planned obsolescence.”

2. Price Fixing: The members of the Cartel coordinated their pricing strategies to maintain higher prices across the board. This practice eliminated price competition, which could have benefited consumers.

3. Market Control: The Cartel sought to control the market by restricting the entry of new competitors. This included sharing information about production techniques and collaborating on marketing strategies to strengthen their collective position.

The Phoebus Cartel’s actions had far-reaching consequences for consumers and the lighting industry. While the Cartel succeeded in maintaining high profits for its member companies, it stifled innovation and limited choices for consumers. The enforced obsolescence of light bulbs meant that consumers were forced to spend more money on replacements, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction.

Moreover, the Cartel’s practices delayed the introduction of more efficient lighting solutions. It would take considerable engineering efforts to develop the shorter lived bulbs, so these companies focused their engineering time and resources on the short life bulb products, ignoring other state-of-the-art technologies. This emphasis on short-lived products meant that advancements in energy efficiency and sustainability were sidelined for decades in favor of short-term profits.

On paper, the Cartel’s mission sounded entirely benign. The document that the companies signed to join was called the “Convention for the Development and Progress of the International Incandescent Electric Lamp Industry.” According to that document, the organization’s chief goals were “securing the cooperation of all parties to the agreement, ensuring the advantageous exploitation of their manufacturing capabilities in the production of lamps, ensuring and maintaining a uniformly high quality, increasing the effectiveness of electric lighting, and increasing light use to the advantage of the consumer.” It covered all electric light bulbs used for illumination, heating, and medical purposes. In addition to the companies mentioned earlier, other members included Hungary’s Tungsram, the United Kingdom’s Associated Electrical Industries, and Japan’s Tokyo Electric. The U.S. company GE, one of the prime movers behind the group’s formation, was itself not a member. Instead it was represented by its British subsidiary, International General Electric, and by the Overseas Group, which consisted of its subsidiaries in Brazil, China, and Mexico.

The Cartel’s efforts did produce some positive results. The major global bulb companies were able to facilitate the exchange of patents and technical know-how to impose far-reaching and long-lived standards. To this day, we still use the screw-type socket, designated E26/E27, that was developed by Edison—thanks to the Cartel.

The Phoebus Cartel’s reign began to unravel in the late 1930s as public awareness of its practices grew. Investigations into the Cartel’s activities revealed the extent of its market manipulation. In 1941, the Cartel was officially dissolved under pressure from regulatory bodies and changing market dynamics.

The legacy of the Phoebus Cartel serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of monopolistic practices as well as the importance of competition in fostering innovation and protecting consumer interests. It highlights the need for regulatory oversight in industries where a few powerful players can exert significant control over the market.

The story of the Phoebus Cartel is a fascinating chapter in the history of the lighting and consumer products industry, illustrating the complex interplay between corporate interests, consumer rights, and technological advancement.

Featured image courtesy of Steve Collinge.